Double-click to edit text, or drag to move.

Double-click to edit text, or drag to move.

Double-click to edit text, or drag to move.

Double-click to edit text, or drag to move.

Double-click to edit text, or drag to move.

Double-click to edit text, or drag to move.

Double-click to edit text, or drag to move.

Double-click to edit text, or drag to move.

Double-click to edit text, or drag to move.

Double-click to edit text, or drag to move.

Double-click to edit text, or drag to move.

Double-click to edit text, or drag to move.

Interesting article in the 2009 Soundings:

http://www.soundingsonline.com/columns-blogs/under-way/237632-under-way

_______________________________________________

Reprinted from the 1980 Nautical Quarterly Number 12 with permission. Assistance was provided by Chris Ward.

Rough Day Off Old Man Shoals

When the November winds sweep over the sandbars near Nantucket, only fervid fishermen venture out for striped bass that swarm there

Sports Illustrated November 18, 1968

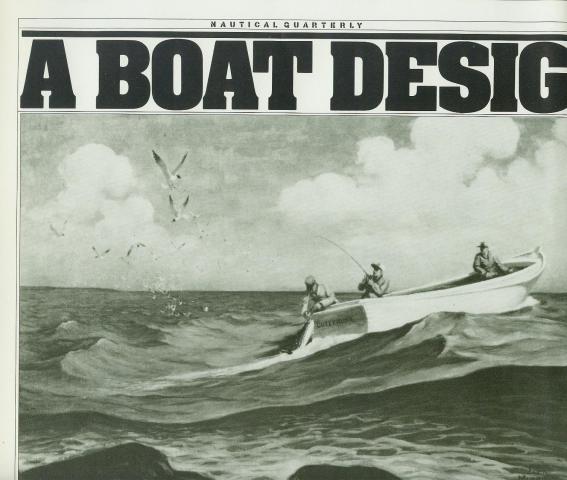

Thirty-five miles south of Cape Cod's elbow, just off the southeast tip of Nantucket Island, a 10-mile-long stretch of shifting sandbars called Old Man Shoals churns the Atlantic into a convulsive horror for boatmen. It is cold off Nantucket in late fall. When the wind comes down from the north or northeast, Old Man Shoals is not a good place to be—that is, unless you happen to be a striped bass or one of that obsessed army who must pursue this most charismatic of East Coast game fish regardless of the cost. Why the name Old Man Shoals? No one seems to know, but after spending a day there in a November gale I offer this explanation. It is called Old Man because of the way it makes you feel when you fish there this time of year. You are soaked and chilled from a biting shower of salt spray, bruised and sore from being thrown around in the boat's cockpit by mountainous waves and, woe of woes, seasick.

In November, over the bars and shoals of Nantucket's east and southeast shore, huge schools of migrating stripers linger on until the third week of the month in some years, long after others of their species have yielded to cold water and northeast storms and disappeared to the south. No one is certain why they remain or from where they have come; but they are there, and they are hungry. Mindful of the market price of the delicately flavored bass, a few charter-boat skippers single-mindedly chase them from dawn to dusk through waters that would keep a destroyer at dockside. Their sport-fishing parties gone for the year, these modern Ahabs head for Nantucket and a physically taxing combination of sporting and commercial madness.

The most persistent and well-known of the striped-bass zealots is Irving (Bud) Henderson, skipper of the 30-foot Mackenzie bass boat, Li'l Darlin', based at Harwich's Wychmere Harbor. A Boston outdoor writer who had gone out with him a year ago reported that in less than seven hours they had landed 1,000 pounds of bass, some as large as 35 pounds. All but a few of the fish had been taken on handlines. I wondered what a big bass would feel like at the end of a handline, with no reel drag or rod to absorb its powerful rushes.

Bud Henderson agreed to take me out the first week of November; we would leave the harbor before dawn. At 2:30 a.m. the thermometer at my home outside of Boston read 36�, and I remembered it was November and I was going fishing 30 miles at sea. I had been ice fishing in warmer weather.

At 5 a.m., in the dark beside the pier, the radio in Bud Henderson's boat forecast northeast winds from 25 to 35 mph, the perfect prescription for trouble in the waters we were to fish. The skippers of two other boats listened to the forecast and climbed into their cars and went back home to bed. But Henderson had been averaging about $100 worth of bass each day, and he was going fishing. Heading into dark Nantucket Sound, the boat rose and fell in six-foot swells, and three or four times each minute it was like coming to a sudden stop in a high-speed elevator. At 6:15, while going through a rip west of Monomoy Island, a wave broke completely over the boat. Waves of 10 to 12 feet crashed wildly by on all sides, "Look ahead!" Henderson shouted. "Don't look back unless you wanna get scared. You know who the smart fishermen were today, don't you?" he added. "The ones who stayed home. It's too rough to turn back, so we might as well fish." I grinned weakly, trying to ignore hints of wooziness at the bottom of my rib cage.

Now it was light enough to see seven or eight miles in any direction, and in all that water ours was the only boat. Bob Luce, a Boston machinist who hadn't gone a week without striper fishing in eight months, ducked into the cabin and came out with five 125-foot coils of nylon monofilament handline, three testing 180 and two testing 80 pounds. To each of these was tied a size 7/0 lead-head No-Alibi lure.

Three miles to the southwest Nantucket's Great Point was visible for the first time. The previous Friday afternoon Henderson had taken 1,280 pounds of bass, including a 54-pounder, from the rips just west of the point. We cruised slowly two miles off the beach. Once I was sure I had seen at least an acre of feeding bass on the other side of the rip, and Al Ristori, a Garcia Fishing Tackle representative, kept seeing diving birds. Bud Henderson called no false alarms though, and we perked up when he suddenly gunned the engine and pointed to the southwest. Just over a mile away, what looked like a little cloud with a thousand wings was hovering over a very rough stretch of water. This was our first glimpse of Old Man Shoals.

Three of the lines were fastened to points along the stern, and the other two to 14-foot outriggers. Foot-long pieces of heavy, stretchy rubber at the boat end of the lines would act as cushions against the strikes of large fish. Henderson tipped each lure with a five-inch strip of pork rind, and as the boat neared the rip we threw all five lines over. We stood with our legs braced against the gunwales of the pitching boat, jerking the lines back and forth to make the lures breathe, and waiting tensely and expectantly.

We edged alongside the shoals, and suddenly there were fish flying through the air, bouncing off our backs, hitting against our legs. In less than two minutes eight bass flopped onto the deck. None was under 10 pounds; one was more than three feet long and looked to be at least 30 pounds, far larger than any I had ever caught. It was a mesmerizing scene and all I could do was stare at the fish.

Henderson's voice cut short my reverie. "Hey, grab your outrigger line," he shouted into my ear as he lobbed a 15-pound striper into the fish box. I snatched the line from the outrigger, jerked in a foot or two and then had it yanked away. I felt like a child with a Great Dane on a leash. It was embarrassing. Bob Luce had two more bass in the boat and I was still working on this one. Luce edged over, and together we hauled the fish, hand over hand, to the side of the boat, where Henderson gaffed it, a 27-pound striper. I was uneasy killing such a wonderful fish without giving it a real chance.

For a moment I watched other bass being drawn toward the boat—making short, powerful rushes, futile against the heavy line—and then being yanked over the gunwales to beat out their lives in the fish box. Some of the bass had been hooked deep in the gills, and there was blood everywhere. Once when we edged into the main part of the rip I slipped twice on the deck of the wildly lurching boat. Each time I rose and grabbed the line—throbbing with life—from the outrigger pole. Now in the mood and getting the knack of retrieving the line with long, tightly gripped strokes, I managed to boat a 10-and a 15-pound bass and to grab an unmanned stern line and haul in the first of the day's four bluefish.

Suddenly the fish stopped striking, and the birds that had been hovering just at the wave tops now rose high in the air and spread out over perhaps three acres to search for a new feeding area. A fish box four feet long, four feet deep and three feet wide had been filled with bass, and seven or eight more lay on deck.

As we began heading slowly southwest along the seaward edge of Old Man Shoals we hit even rougher water, and my stomach began to turn again. Every two or three minutes the boat would sink into a trough between eight-to 10-foot swells, and in an effort at forgetting my stomach I decided to take a picture of the men in the stern with the water curling above their heads. I started to get up to take a meter reading, but this was a mistake. My feet shot out from under me, and my head hit the wall below the steering wheel. Though stunned and not fully aware of what had happened, I was sure the boat had capsized and wondered why I wasn't under water. Seconds or minutes later, I felt a cold hand on the back of my head and opened my eyes. The hand was the tail of a big striper, one of about a dozen that had flown out of the fish box. No one at the stern had seen me fall. They were fishing again, and were landing fish. In the time that I was floundering on the floor we had reached another school.

Possibly the loveliest sensation known to man is the emergence from seasickness. My recovery began during a long run through relatively calm water. Henderson had discovered a bottle of Dramamine in the cabin, and I swallowed one. I stepped toward the stern, where the cold wind in my face had a stimulating effect. Fifteen minutes later we were off Nantucket's southern shore, at the western end of Old Man Shoals, and I was raring to fish.

Birds had begun feeding well inside the shoal's edge. We should never have entered the area without safety belts. No amusement park would be allowed to have the kind of ride the Old Man gave us for the next hour. It was not possible to stand unsupported and erect for two consecutive seconds, and I wedged myself, down on one knee, into a corner at the stern, one hand jigging a handline and the other with a death grip on one of the gunwale's mooring rings. The others, more adept at offshore gymnastics, stood against the stern, knees bent and legs spread wide. The bass appeared on cue. Whack! I had a hard strike, released my handhold, began standing to land the fish and went over on my backside as the boat tipped 45� left, sliding me into Bob Luce's legs. Luce, who was also landing a fish, sat down on my stomach. All five handlines had been struck, and as we groped for the lines and got them close to the boat, the bass seemed to take advantage of our chaos and swam around each other, weaving four of the lines into a freestyle cat's cradle. In the next half hour nearly 25 more bass wound up in the fish box, and our seagoing slapstick continued. It was only 37� now, and our faces, whipped by the wind and a combination of spray and rain, began to look like ripe tomatoes.

Through it all Bud Henderson constantly ran from wheel to stern, landing fish, changing our course, manning the tiller, speeding us up and slowing us down and untangling lines. He seemed to have suction cups on his feet and a gyroscope in his head. He was not the slightest bit concerned by the roughness of the sea. During a lull in the fishing Bud talked about his greatest day, in November 1965. "All alone I caught 3,750 pounds of bass, 237 fish averaging 12 pounds. The cockpit was full of bass. The cabin was full of them. They were spilling onto the bunks and into the sink and all over the floor of the head. The next morning a friend went out with me. 'I know you're a good bass fisherman,' he yelled from the cabin, 'but I didn't know you were this good.' He walked out holding three bass I hadn't found the night before. 'We haven't even started fishing yet,' he said, 'and you've already caught three fish.' "

Feeding stripers, especially in the fall, are often all over the place one minute and gone the next. Now the fish had stopped striking. Our hands were stiff from the cold, the ocean was even rougher than before and, though we waited and hoped, the wind had not switched from north to south as predicted at dawn. We would have to buck wind-driven surf and gusts of gale force for nearly 40 miles going home. Henderson reacted predictably: he started looking for more fish. But there was no recklessness here. The Li'l Darlin' is a bass boat built to chase its quarry into the meanest water, and the sea poses little threat to its 55-year-old skipper. For most of the last 32 years—May through November, time off only for hurricanes—the sea has been his dawn-to-dusk, seven-day-a-week office. If there are fish within his cruising range, he fishes. Soon the bass would be gone and, though there would be winter scalloping and quahoggmg, the checks would be much smaller and maybe not as frequent.

We continued fishing, but with no luck. A voice over the marine telephone called Henderson to the cabin. It was a friend who was fishing off Great Point, 15 miles closer to home, and who was concerned about the Li'l Darlin' and her skipper: "It's real bad up here, Bud, really gettin' heavy. Hey, you might wind up spendin' the night on the island."

They small-talked a few minutes, Henderson deliberating. "We're going in now," he said finally, hanging up. "Pull in the lines," he shouted. Then, as an afterthought, he added, "But don't put 'em away. We might hit fish on the way home."

We headed inshore to avoid Old Man Shoals, rounded Nantucket's southeast corner and headed north toward Sankaty Head, or so the compass indicated; our movement was more of the up and down variety. About halfway to Great Point things began taking a turn for the worse. If Dante's Inferno had been a sea saga, a panoramic view from our stern would have been the perfect cover-jacket photograph. The wind was blowing the tops off waves and filling and refilling the cockpit with foam. Now there were 10-foot swells, higher and steeper than in the morning, and at the bottom of each we lurched to a dead stop, provoking an uncontrollable "oooph" each time from the pit of my stomach. I sat next to the cabin with one hand on the door and the other supporting my head, which bobbed weakly and resignedly up and down, and constantly reminded myself that the passage of each miserable minute brought us closer to land. Bud Henderson stood at the wheel, operating the manual windshield wipers, speeding up or swerving to avoid a breaking comber and eating apples. His was the stoic calm of a man who has taken the worst the sea has to offer and never even been seasick. "A fisherman's life is a rough one. It's a wet butt and a hungry gut," he says wryly. "Whether you catch 'em or not, you still gotta go out the next day."

Three-quarters of an hour later and two miles to the northeast, we could see the southern tip of Monomoy Island, a lonely 10-mile-long bird sanctuary dangling south of Cape Cod. Monomoy! Oldtime bass fishermen speak of it in hushed tones. Fishing on the island can be so explosive at certain times of the year, that occasionally, in the past, impatient beach-buggy operators haven't bothered to wait for the oyster barge at Chatham and have tried to drive across the flats at low tide. Some have made it, but if you stand on the beach at Chatham Inlet when the tide is out you can see the buggies of a few that didn't, now rusted, wrecked derelicts sticking up out of the mud.

After leaving the tip of Monomoy behind, we entered the relatively sheltered waters of northeastern Nantucket Sound, and soon the low line of Cape Cod's southern shore loomed out of the overcast horizon. By the time we entered Wychmere Harbor four large boxes had been stacked to overflowing with fish, and half a dozen more bass in the 30-pound class lay in the boat. Stripers are handsome fish, firm and strikingly colored. They don't fade quickly, as do many other species, and now, four to 10 hours after being caught, they were still beautiful, all 700 pounds of them. But at the moment my esthetic needs were territorial, not piscatorial. Above all I craved the feel of land beneath my feet. I climbed onto the dock, thanked Bud Henderson and walked to my car. Maybe by next May I would want to look at another striped bass.

The next day, after a good night's sleep in a warm bed, Old Man Shoals seemed a universe away. I joked about having been seasick: it could never happen again. Indian summer had returned, the forecast called for more of the same for at least a few days and for the waters off Cape Cod winds no stronger than 20 mph. All day I thought of the 27-pound striper I had caught on a handline and of the even bigger ones that were surely still there. The next time I would bring a light surf rod. The next time? That evening I phoned Bud Henderson and made arrangements for later in the week.